Indigenous Group Theory Working Blog

Background and Goals

My inspiration for this project of mine comes from my former supervisor, Dr. Yu-Ru Liu at the University of Waterloo. Each term, she runs a Directed Reading Program for women and people of underepresented gender identities in the math faculty at UW. Undegraduates are matched with graduate students, where they will work through a "reading project" of sorts. The aim is to get more women to pursue graduate level maths.

When I started to think about this, as far as I was aware, I was the only Indigenous masters student at SFU, so I thought that it would be great to have a program like the Directed Reading program at SFU, but for Indigenous math students instead, to encourage more Indigenous math students to pursue graduate math. As it turns out, I'm the only Indigenous math student at any level at SFU. There goes that idea...

After doing quite a bit more thinking, and with the interest of at least one Indigenous psychology student at SFU, I decided that I wanted to change up the vision of the program to be open to any Indigenous student at SFU, where I assume no math background and we will dive into math topics. Group theory seems like a good fit for a program like this, because it can be very visual, concrete, and hands-on.

My current goal is to be able to talk about the wallpaper groups and to classify them in the workshop. How much proofs we will do or how rigorous they will be, I'm not sure.

Ideas

Like I've mentioned, I'm not sure what this is going to look like yet. Here are some ideas.

Two of the biggest resources I've been looking at are "Groups and Symmetry" by M. Armstrong, and "Visual Group Theory" by N. Carter.

I was reading the section of this conference article, Edward Doolittle, Lisa Lunney Borden, and Dawn Wiseman discuss a number of different things about Indigenous math. One thing that stood out to me was the language that we use to talk about math. Most of the words that we use to describe math, in English at least, are very static, i.e., math terms are more noun based than verb based. One of the examples that they use is that, in Mi'kmaw, there is no word for "flat" in the sense of a flat surface, like that of a prism. So how do you define what a polyhedron if you can't even describe what the sides are? One grade three student that they worked with remarkably said "It can sit still!" As it turns our, this is essentially what the greek word "hedron" means in the first place, but this has been lost over time. Teaching through verbs instead of nouns could be the key. They go on to give more examples, such as lines, slopes, and even infinite sets. Instead of asking "what is the slope?" we should ask, "how is the graph changing?" Of course, these mean the same thing, but to someone who isn't comfortable with the vocabulary, the latter is more approachable.

I think this is how I'll teach group theory. That is, through actions. Of course, actions are very natural in group theory. Groups act on other objects almost by definition. Some of the simplest examples of groups are the dihedral groups, describing the symmetries of regular polygons. The group elements themselves are the actions that we can do to the polygons that preserve them. Another simple group is the symmetric group, which describes the action of rearranging lists of objects. Even the simplest groups, the cyclic groups, which are usually just thought of as the groups of modular numbers, can be thought of as describing actions. For example, just looking at the rotations that preserve regular polygons give us the cyclic groups.

I think that as far as the actual group theory material goes, I'll roughly follow Visual Group Theory, but I also want to integrate some cultural stuff into the workshop, such as beading.

Some thoughts as I'm writing this just came: If you have a bracelet with a pattern that repeats \(n\) times, then this can replace an \(n\)-gon when coming up with the cyclic groups. Maybe what I should do through this is figure out a way to introduce each of the concepts through culture, this being a way to introduce the cyclic groups, and then have the participants read something. We can bead practically any shape and look at the symmetries to find the dihedral groups. Given a set of beads, we can think about how we can rearrange the beads to introduce the symmetric groups.

Once you have subgroups and orbits, neither of which I'm sure how to introduce, you get cosets for free, since these are just the orbit of a subgroup acting on the group. Since we have cosets, with a little discussion about conjugates (or something equivalent), we have quotients. Quotients themselves, and maybe some talk about isomorphisms might be enough to dig into the wallpaper groups.

We might be able to get some pretty beadings inspired by some of Carter's diagrams in Visual Group Theory. I really like figure 8.14 depciting the first isomorphism theorem on \(A_4\)

There's this interesting problem that I've encountered a few times when trying to think about basic groups. This confused me when I was learning, and it still confuses friends of mine that aren't in math, even if they have a strong math background. The first way that I learned groups and the way I always ry to explain this, is through symmetries of regular polygons. For example, there are 6 symmetries of a regular triangle. The group elements here are rotations by 60, 120, and 360 degrees, and a reflection followed by one of these rotations. The glaring problem is as follows: "is the group representing this the result of the applying the symmetries or the symmetries themselves?" Of course, if you've worked through group theory more rigorously, then you know that it's the actions themselves. But if you're simply trying to visualize group theory, to remove the algebra from it, why should this be the case? Why can't it be the result of the symmetries if you give the verticies labels?

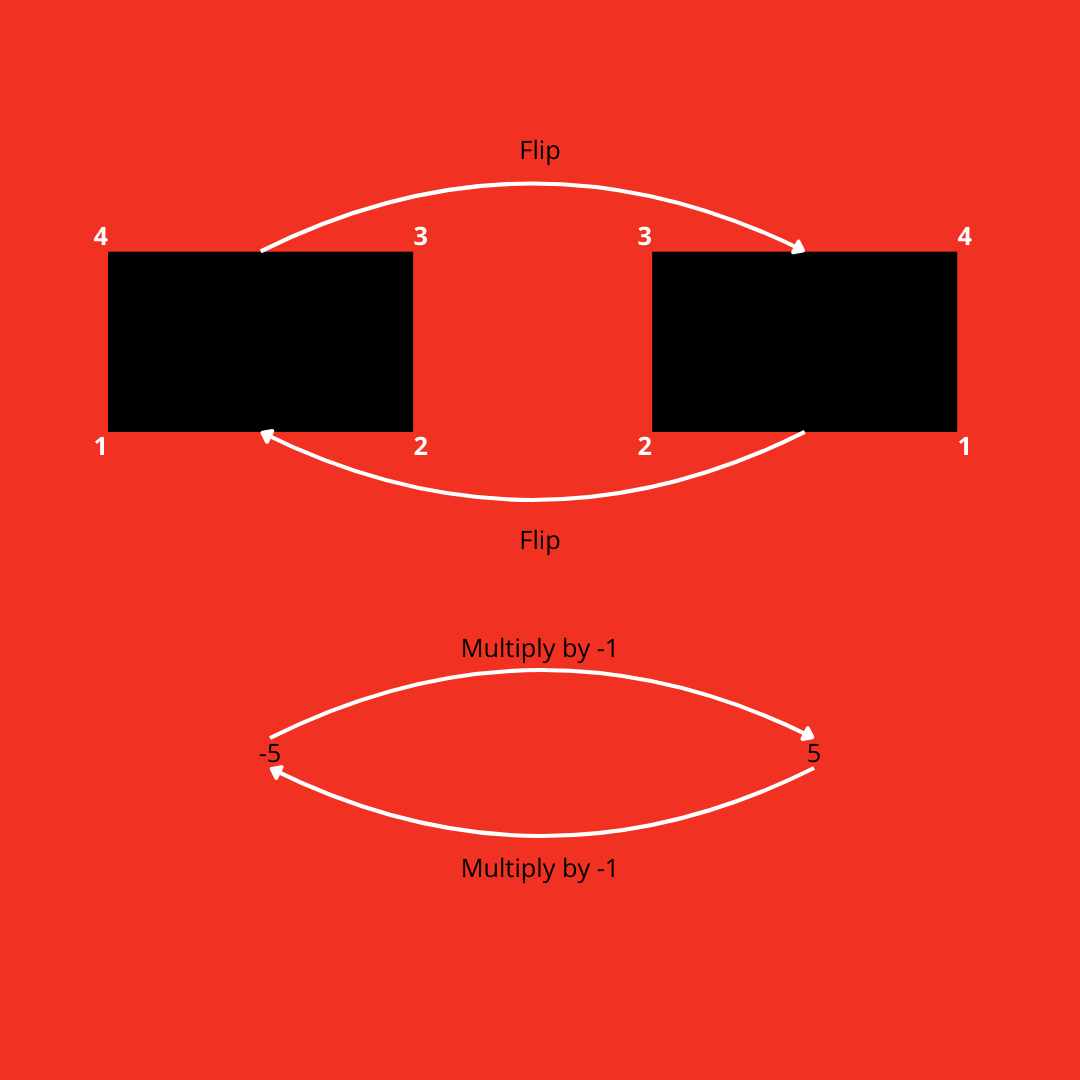

A pervasive theme in abstract algebra (and the foundation of category theory) is relationships. In math, we usually denote these relationships using arrows.

Here's two relationships. The first relationship is flipping a rectangle. A completely different relationship is multiplying a number by \(-1\). However, if we get rid of the words on the arrows and even get rid of the objects that we're acting on and replace them with circles, then these two situations look exactly the same. We can say that the two different situations/relationships are isomorphic.

I suppose a small outline of what I intend to do is in order.

- Exploring symmetries

- beading symmetries: D2, D4 are Abelian, D6 onwards aren't - get people to notice and think about this

- Cayley diagrams

- Group generators

- Drawing relationships

- Abstracting: turning objects into nodes and relationships into arrows

- Brief isomorphisms - same cayley diagrams

- Orbits and cycle graphs

- The symmetry of abelian cycle graphs

- Subgroups

- pg. 101; (1) and (5) both generate C6, does (2)? (4)? (3)?

- Cosets

- Use some of the beaded creations to explore this. If you start at a particular element and do the same multiplication over and over, which elements do you get?

- The cosets are a partition

- All cosets are the same size - get people to notice this themselves

- Direct Products

- Quotients

- The quotienting process from the book - collapsing cosets to points

- Symmetries of the plane: Euclidean group

- Rotations and Reflections are symmetries again, but if we no longer have bounds, what else can we get? (Translations)

- Translations are a subgroup of E2

- We can describe the symmetries of an infinite wallpaper by a subgroup G of E2.

- Following Armstrong, \(H = G\cap T\) and \(J=\pi(G)\) where \(\pi\) is the projection onto the Orthogonal group (group of reflections and rotations)

- A Wallpaper group is a subgroup of \(E_2\) if \(H\) is generated by two independent translations, and the point group is finite

- The point group of a wallpaper group is generated by a rotation of either 0, 60, 90, 120, or 180 degree rotation, and possibly a reflection. Get people why must this be the case?

- There are only 17 different wallpaper groups.

Jan 15, 2025

After meeting with the department chair and talking about the ideas that I have for this workshop, I have quite a bit to think about. One of the biggest things that I took out of the meeting is that I need to ensure that culture is on the same level as math. Do not simply impose the western math language as a new way to describe what's going on in the beading things or any other cultural component that I am doing. One of the examples that he gave was from when he was doing a basket weaving workshop a few years ago. He had become very excited because he was able to write down a series of mathematical operations that perfectly described one of the patterns on the basket that his colleague had made. Her reaction was, "So what? This does not describe anything that I have done." This is something that I hadn't thought of before. Of course, we can look at examples of math in culture, and then describe the culture using math, but it may not describe what is really going on. We shouldn't just be using culture as examlpes, otherwise we give off a very colonial vibe.

I think that I need to learn how to bead before I move on. Of course, I've known that I need to learn, because I want to include this in the projects. But maybe there is something in the process itself that I can learn from and include.

To those that choose to join me in my workshop, chi miigwech. You may have never thought of yourself as a mathematician, or as someone who is good at math, but perhaps it is now that you are blooming in maths. It may not have happened at the same time as others, and maybe even now is not the time, but each of us can bloom in time. (Inspired by a quote from Dr. Florence Glanfield and Dr. Edward Doolittle)

Jan 14, 2025

Possibly an idea for demonstrating generators of a set. It's quite typical for the group of us in the ISC or in FNMISA to be sitting around a table. Maybe Joseph is sitting across the table from me and I need to tell him something. The obvious thing to do is just to speak to Joseph from across the table. But what if the table is too big or if the table is too loud? How else could I get my message to Joseph? I could communicate in smaller distances. Maybe Evan is sitting next to me and between Evan and Joseph there is April. I could tell my message to Evan and then Evan tells my message to Joseph since he's closer. He could also tell the message to April, and then April tells it to Joseph. So the action of giving a message to Joseph is the same as giving the message to Evan, then Evan to Jospeh, or to Evan, then Evan to April, then April to Joseph. (J-J = J-E, E-A, A-J = J-E, E-J) Simply by speaking to the person next to me, I can get a message anywhere around the table. So we can say that the action of speaking to the person next to you generates the group of speaking to people at the table.

Is this the only way to guarentee that a message can get to anyone at the table? Suppose the table has 9 people around it. Can you find any other generators?